2024-06-24

The Most Hated Device in Healthcare Part 2

Beyond Record-Keeping: The Expanded Influence of EHRs in Healthcare

In this second post of our series, 'The Most Hated Device in Healthcare,' we trace the evolution of hospital systems from fragmented, departmental tools to integrated enterprise solutions. As a firsthand participant in the development of EHRs, I've witnessed their growing pains and transformative potential.

Best-of-Breed to Enterprise

As computer systems grew in healthcare, they were isolated systems within a hospital. Systems were sold at the department level for each department's function. These department heads would pick the software system that was the best for their area, resulting in a best-of-breed era. There was a lab system, a radiology system, and billing. These systems were from different companies and did not talk to each other.

As integration between previously isolated systems—like labs and billing—began, the complexity increased significantly. This integration was essential for creating what we now know as enterprise EHRs, which allow different hospital departments to communicate seamlessly.

Digitizing the Industry

Remember that this was in an era when Windows on a computer driven by a mouse was brand new. Most people had not interacted with a computer, and a right mouse click was considered an advanced action.

During this same era, two Midwest healthcare tech companies, Cerner and Epic, were building Windows-based EHRs. I was one of the original 20 architects working on this. We were taking paper processes and creating screen versions of the workflow. By today's standards, a "rethink the process" would be most people's approach, but back then, there were no UX designers and no software patterns.

Oh, the Complexity of Healthcare

Healthcare is complex, and things aren't always straighforward. Communication between roles has many unwritten rules. A physician giving a nurse a verbal medication order that goes to the pharmacy is ripe for miscommunication. Once we digitized things, people wanted it to be simple.

We had debates with physicians, nurses, and pharmacists in the room. The pharmacists wanted the physician to state whether an oral med was a tablet, a capsule, or a caplet. The physicians would say they don't care, or what if the physician ordered a name brand, but the pharmacy only had the generic? The time the nurse would give a patient a medication was different from the exact time that the computer said to give it (ex., many patients on the floor would need a BID med at 0800). So, how would the computer system handle "late" charting? How far back should that be allowed? These conversations were not technical; they were all workflow issues that took years to design and resolve. The wider the EHR computer systems spanned, the more complex the design.

The electronic medication administration record called the eMAR, was and still is where nurses would go to see which medications needed to be given to a patient and then chart that it was given. Change can be challenging, and many nurses, especially the older ones, stated they would quit if they had to use a computer. And some did.

In 1999, the report To Err is Human was published. The headline was that 98,000 deaths occurred every year in the United States due to medical errors. This report was mind-blowing for almost everyone. The findings identified that many errors occurred when a patient changed levels of care, for example, getting admitted to the ER, transferred to another floor, or discharged from the hospital. There was a communication gap, and regulation was implemented for technology to help, resulting in medication reconciliation.

There were many other layers of regulations, such as HITECH, Meaningful Use (all of them), and the 21st Century Cures Act. The systems continued to add more functionality, as well, such as eRx, structured care plans, and order sets.

Orders, The Action of Healthcare

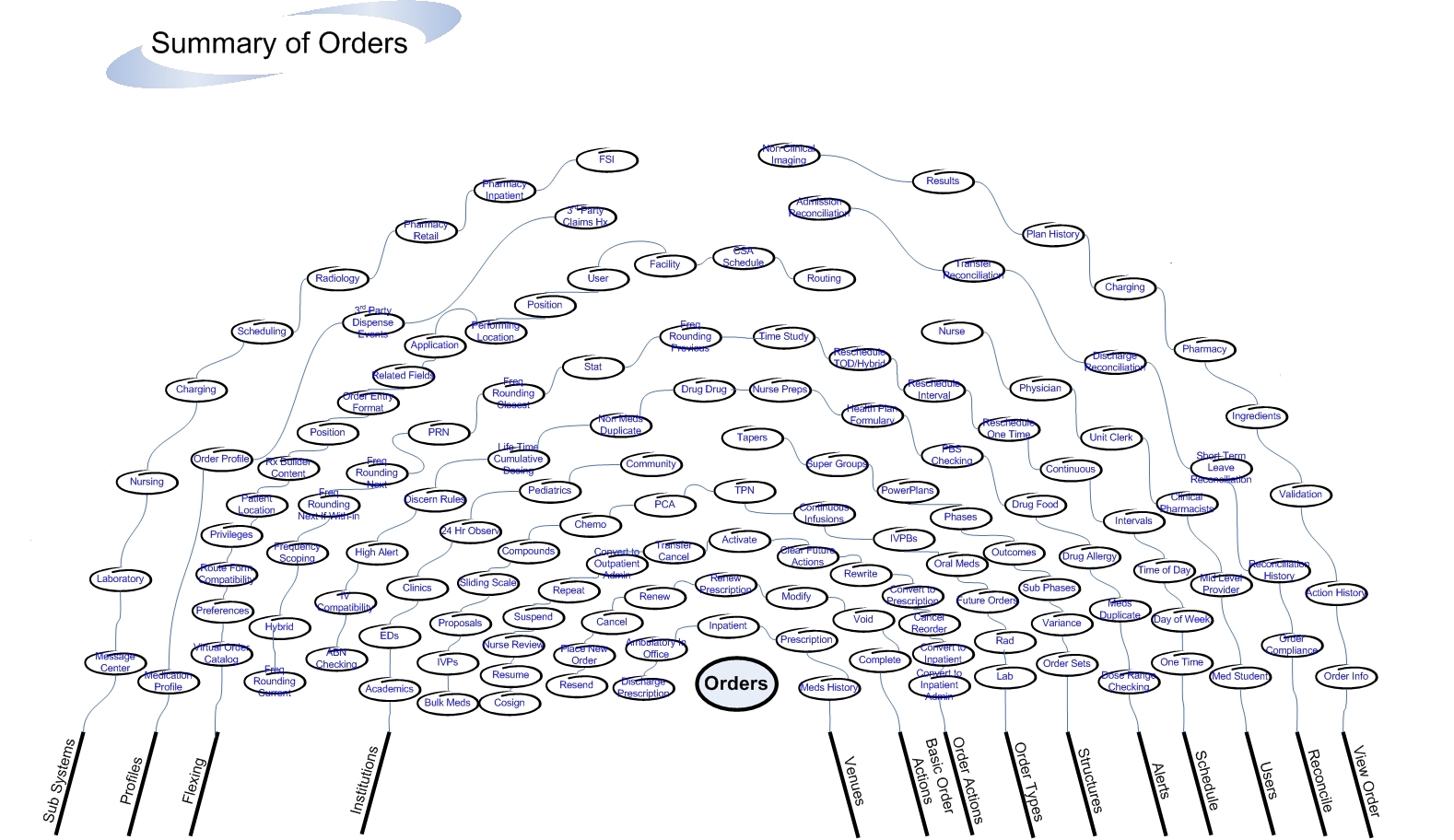

Things were becoming more integrated, and more things happened within the EHR process. For example, ten years after the nurses adopted the eMAR, EHRS introduced computerized physician order entry (CPOE). The physicians resisted. The system was complex and slowed them down. Orders are the action of healthcare. They are core to most workflows. Take a look at the following diagram of orders. It shows many of the different venues, actions, order types, and structures pertaining to orders. Beyond that diagram, there are millions of lines of code. Now, imagine a physician trying to get their job done efficiently. You can imagine the complexity.

It made the hospital as a whole run more efficiently, but there were consequences.

User satisfaction was never part of the regulations; everyone was just trying to solve the complex problems. Ease of use was usually not the highest priority.

Mouse Thrown

It was 1998, I was 25. I was at a hospital during its go-live event. A physician in a hurry scurried to a computer to look something up in the EHR. Within about sixty seconds, he got extremely frustrated. He was not able to easily accomplish whatever he was trying to do. He saw me standing there and started to yell. He then took the mouse and threw it at me as hard as he could. Luckily for me, it was the era before cordless mice, so the mouse flew about 18 inches and crashed into the desk. The physician stormed away. At this moment, I realized the impact that software can have on people. It can enable the impossible, or it can create friction and rage. From that point forward, I focused more on usability in everything that we built.

With all of its warts, the EHRs have transformed patient care. Paper charts are pretty much a thing of the past. The speed of communication across the health system is incredible. When a physician signs an order, it puts many downstream departments into action. The reliance on nurses using chalkboards as a place to document vitals is a thing of the past. Even though there is much to be desired regarding usability, the EHR provides tremendous value to clinicians.

Conclusion

As we reflect on the evolution of Electronic Health Records (EHRs), from their inception as isolated departmental tools to their role today as comprehensive, enterprise-wide systems, it's clear that their journey mirrors the broader technological advancements across many industries. These systems have expanded beyond simple record-keeping; they are integral to orchestrating care across diverse healthcare environments.

The transformation brought about by EHRs has not been without its challenges. The transition has demanded considerable adaptability from healthcare professionals. Large changes are a stark reminder of the frustrations that can arise when systems do not effectively meet user needs, underscoring the importance of focusing on usability and user experience in EHR design. These aspects were often overshadowed by the pressing need to meet regulatory requirements and implement complex functionalities.

Hopefully, this post sheds some light on the complexities of the EHR and how we got to where we are today. It's not an excuse for why EHRs are hated; we'll explore more of that in my next blog post, "The Hidden Cost: EHRs and the Rising Burden on Clinicians." It simply shows the many forces that were at play when building something at this scale.

In the meantime, I'd love to hear about your experiences, good or bad, with EHRs and if you've ever had a "mouse-thrown" moment.

Chuck Schneider is a thought leader in healthcare tech. He was one of the original architects of a major EHR and has 11 patents. When he is not thinking about healthcare, you can find him outside, engaged in some adventure.